Guest writer Stephen Roberts takes a look at the life and works of Shrewsbury’s most famous citizen – Charles Darwin.

It’s perhaps hard to believe that 2015 marks 90 years since Charles Darwin’s theory of evolution was outlawed in the American state of Tennessee. In 1925 – over 40 years after his death – the teaching of Darwin’s work was forbidden on religious grounds and still today, the debate about the theory within US education continues to rage. Yet here in the UK, Shropshire’s most famous son was voted one of the greatest Britons in a BBC poll, and his groundbreaking work forever changed the way humankind thinks about its origins.

Darwin was a Shropshire lad, born the fifth of six children in Shrewsbury in 1809 to a wealthy and well-connected family. The son and grandson of doctors, Darwin was also a maternal grandson of Josiah Wedgwood, founder of the world-famous pottery. It’s said Charles’ paternal grandfather Erasmus Darwin also speculated on evolution, and young Charles spent the first 27 years of his life living in a liberal household which encouraged and fostered his enquiring mind.

A talent for botany

After studying at Shrewsbury School, Darwin studied medicine in Edinburgh, before enrolling at Cambridge, where, ironically, he learned divinity for a church career, having realised he wasn’t cut out to be a doctor. It was here in 1831 that Darwin caught the eye of botanist Professor John Henslow, who recommended him as naturalist aboard HMS Beagle, sailing under Captain Robert Fitzroy on a scientific study in South American waters.

Darwin was away on this voyage for almost five years, and it provided the building blocks for the theories that were to come. Whilst at sea, he read Charles Lyell’s fossil theories. Growing up in Shropshire, it hadn’t escaped Darwin’s attention that the county contains rocks from many different periods of geology; the coral reef that is now Wenlock Edge yielded marine fossils demonstrating the world was much older than people had thought. Lyell’s conjecture – of a process of gradual change over millennia – backed up these nascent speculations.

Survival of the fittest

Survival of the fittest

Back in England, Darwin published works detailing the journey’s discoveries and these placed him amongst the ranks of leading scientists by the mid-1800s. He focused on variation and interbreeding, heading unerringly to conclusions which would shake the establishment. He explained that animals suited to their environment were more likely to survive and reproduce, passing on adapted ‘survival’ characteristics, as the species continued evolving. Influenced by Thomas Malthus’ theories on population, Darwin became convinced natural selection meant the fittest survived, preventing a population explosion amongst species.

Darwin’s great work, The Origin of Species by Means of Natural Selection was published in 1859. It was met with immediate controversy as many, particularly within the Church of England, attacked his theories, which were seen as radical and heretical. There was a famed debate in 1860 between supporter Thomas Huxley and opponent Bishop Samuel Wilberforce on whether man was ‘descended from apes or angels’. Darwin persevered with his studies and his Descent of Man (1871), almost as famous as Origin, took things further by theorising man’s derivation from relations of the orang-utan, chimpanzee and gorilla. In the heightened religious times of Victorian England, it was small wonder some objected. His assertion was trenchant; the difference between humans and animals was one of degree, rather than kind.

Darwin was not the first to speculate on evolution and descent, but he was first to gain broad acceptance for these theories amongst the experts. In getting the story ‘out there’ he elevated it from mere hypothesis to a verifiable theory.

Darwin the man

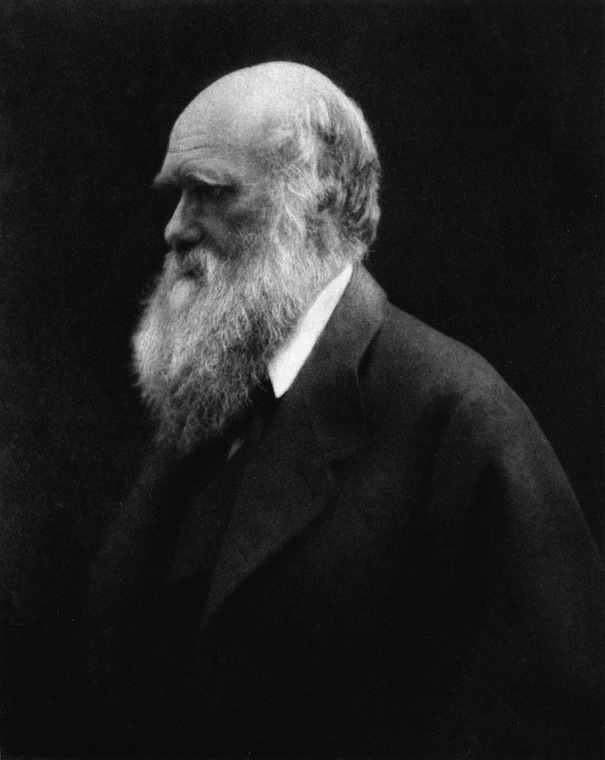

Despite being driven in pursuit of his ‘eureka!’ moment, as a human being Darwin was kind, good-humoured, honest, truthful and an engagingly modest man, devoted to his friends. His resplendent beard makes him a passable Father Christmas to modern eyes. He pursued truth but never overlooked a greater truth that people and behaviour matter. Darwin made a name for himself, but he was not the ‘lone genius’ some have suggested.

Darwin passed away in April 1882 aged 73, and was buried in Westminster Abbey. Stories that he repented of evolution on his deathbed are almost certainly apocryphal. If Darwin could have observed what transpired in the US in the 1920s he may have smiled that the orthodoxy of his time still prevailed; today his ideas are the new orthodoxy.

Today, Shrewsbury hosts an annual Darwin Festival… but this is not a modern phenomenon. In 1909 over 400 scientists gathered to celebrate the centenary of Darwin’s birth and 50 years of Origin of Species. It was unprecedented, but he was regarded as one of science’s most original and prominent thinkers. Perhaps no one has influenced our knowledge of life on Earth quite as much.

Darwin Festival and town trail

The 2015 Darwin Festival will be held between 8 and 22 February.

Darwin would still recognise Shrewsbury today as many of the medieval buildings, shuts and passages he knew still exist – though he might smile to see a statue of himself outside his old school (now the library). The fields and river that surround the town are still open areas filled with flora and fauna to inspire future generations. The festival, arranged by Shropshire Wildlife Trust, aims to ignite curiosity about the natural world and awaken understanding of the marvellous wildlife with which we share our world. For more information about the festival and town trail, visit discoverdarwin.co.uk

Charley Darwin’s Shrewsbury

A new children’s book, Charley Darwin’s Shrewsbury, brings Darwin’s story to life for a younger audience, has just been published by Ellingham Press. The book has been illustrated by Jackfield-based artist Hazel McNab.